Weeks without training. Consecutive days of binging. Terrified to step on the scale.

We’ve all been there.

At this point in my life, I’ve probably fallen off the fitness horse a dozen times or more.

Some people fall of the horse once and never get back on. I’ve seen this with some of my clients, unfortunately; if I don’t get to them before it’s too late, they have dropped fitness for the immediate future.

Luckily, I’ve saved many of them and have been able to iterate and tweak the steps that I recommend.

Here’s exactly how to get back on the horse when you’ve fallen:

Step 1. Realize that falling off the horse is normal

I’ve written a lot about self-compassion, so I won’t beat that horse to death. (Otherwise you won’t be able to get back on it, amirite? What is it with all of these equine metaphors anyway…) But it’s important to show yourself some self-compassion.

Look, falling off the horse is completely normal. Everyone does it, and it doesn’t make you weak-willed or undisciplined. It makes you human. It’s important to come from a place of self-compassion here so that you can try again.

We’re going to go through an exercise that’s used in the field of social work in order to improve self compassion around this situation. It may seem silly, but it will greatly increase your forgiveness for this misstep.

Split yourself up into three different personas.

The criticizer – The person who is angry that you fell off the horse.

The criticized – The person who is defensive about the potentially hurtful things that the criticizer is saying.

A compassionate mediator – Someone who is going to look at things objectively and help figure out how to move forward. You can pretend that this is the most compassionate, understanding friend that you have.

Now, run through the dialogue that the criticizer would say. You know, the things that you’re internally berating yourself about for stopping your regimen. Notice the charged words that are said and how they make you feel.

Secondly, run through the dialogue that the criticized person would say. Talk about how hurtful the criticizer’s words are and how they don’t make you feel like continuing.

Lastly, go through the compassionate mediator’s role. You’re going to show an extreme amount of compassion for the person being criticized. It’s important to note that this does not mean making excuses, but rather, be empathetic and understanding of the situation at hand.

Mediate those two sides. Talk about how the criticizer’s intentions are probably good, but the way that they are expressed hinder the ability to progress. (Remember, the mediator should be compassionate towards both parties.)

Go through a plan of action in which the criticizer will be happy that you’re going to prevent this misstep in the future (This is a good place to run the Time Machine Exercise in order to talk about what you could’ve objectively done to minimize the amount of derailing), and the criticized person will feel supported in his endeavors and understand that he/she is not defined by his misstep.

You’ll find that when you practice going through this exercise, you’ll start to show yourself a lot more self-compassion for falling off the horse.

Step 2. Evaluate your losses objectively, without judgment

Once you show yourself some self-compassion, you can now evaluate your losses objectively, without judgment.

Your losses can be broken down into two categories.

Muscle and Strength Loss

If your layoff was under three months then chances are you did not lose very much muscle.

According to Sports-Specific Rehabilitation, “Strength trained athletes retain strength gains during short periods of inactivity (2 weeks) and retain significant portions of strength gains (88% to 93%) during inactivity lasting up to 12 weeks.”

If you’ve gone without training for longer then that, don’t fret. Bodybuilders and strength athletes have long observed that even after a long period of inactivity outside the gym – sometimes lasting years – previous levels of strength came back relatively quickly. It’s almost as if one’s muscle retains a “memory” of how strong it once was. (Hence, the term for this is “muscle memory.”)

Scientists were actually perplexed about this phenomenon until recently, when it was discovered that the nuclei of muscle actually stays in-tact even through atrophy.

tl;dr – strength comes back quickly.

Fat Gain

If you have been feasting and binging for several days, or even weeks, the number on the scale may shock you. It’s typical for clients to put on as much as 5% of their bodyweight (10 lbs for a 200-lb man). One female client put on 8% additional bodyweight (about 10 lbs for a 135-lb woman).

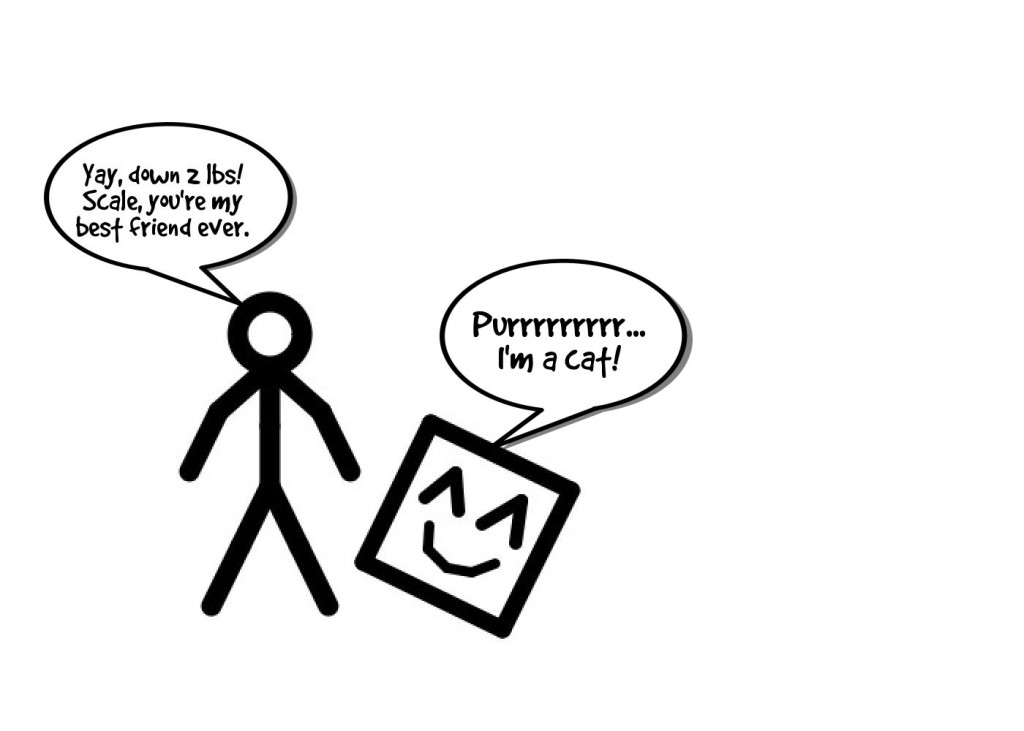

But most of this weight is probably from excess water retention, not fat.

Basically, the scale is lying to you. Realize that it takes a surplus of 3,500 calories to gain one pound of fat. Think objectively and without judging yourself – Do you think that you racked up that much of a surplus?

Possible, but not likely. In all likelihood, most of it is water weight. Take a week on a relatively moderate caloric deficit (20% or so) then step on the scale again so that you can come to an objective conclusion. Additional water weight should subside by this time.

Taking the scale at face value is particularly dangerous without doing the protocol above. I’ve seen clients who fell off the horse completely, because they assumed that they undid all of their progress. In reality it would have only taken a week or two to undo damage.

Often it’s not the two-week vacation that someone takes that leads to their fitness doom, but the illusion that this doom had already occurred.

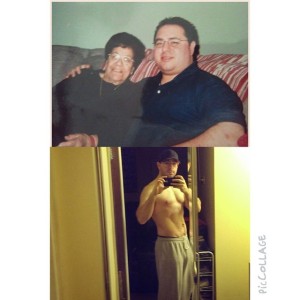

I have personal experience with creating this self-fulfilling prophecy. In 2006, I lost 40 pounds in 4 months and then competed in a bodybuilding contest. After gorging myself for two days straight post competition, I stepped on the scale and saw that I had gained a whopping twenty five pounds. Rather than realize this caloric accounting is impossible, I felt defeated, allowed myself to continue gorging, and ended up weighing 200 pounds within six weeks. (And no, that was not water weight.)

The moral of the story is this: When you fall off the horse, whether you think you’re past the point of no return or not, you are right.

So analyze objectively, without judgment. Better yet, talk to an experienced coach if you don’t feel like you can be objective with yourself.

Step 3. Show gratitude for how far you’ve come

Let’s say you won the lottery tomorrow. You’d be pretty fucking happy, right? Of course you would.

But that happiness fades away quickly. As it turns out, research shows that you probably wouldn’t be happier than the average person, and only marginally happier than someone who was paralyzed in an accident.

When it comes to happiness, us human beings are equally incredibly resilient and stubborn. We are always establishing a new baseline of happiness, and I see this in my clients all the time.

One client went from dumbbell chest pressing 40 lbs to 100 lbs in a few short months. (Honestly, there were some amazing genetics at play here, since that took me a total of 3 years.) Yet, after a short break he was incredibly displeased that he could only do 80 lbs.

When you focus on how much you “once could do” you idealize your past similar to the paralyzed individuals in the study above. (Note: Apologies in advance. I really don’t mean to equate losing 20 lbs on your bench press to becoming paralyzed, rather than display what happens when you idealize your past.)

Idealizing the past will lead to preemptive feelings of defeat, hopelessness, and self-hate.

But this can be prevented by showing a sense of gratitude. Take a step back. Think about how far you’ve come and how much work you put in to get there.

If you show a sense of gratitude with your progress to-date, you no longer focus on the 100 lbs that you used to do, but the 40-lb increase that you’ve accomplished. When you do that, you can again focus on continued growth rather than previous glory.

Step 4. Create a todo for list for “Reboot Week” and establish a baseline

The very last step is to designate a week to get back on your program – we’ll call this “Reboot Week” – and create a detailed list of all the things you have to do.

For example, if you’re struggling with going back to the gym because you’re worried about how weak you’ll feel, then your checklist will look like the following:

Monday

Diet

– Hit macros within +/- 3%

Training

– Put on workout attire

– Get in car

– Drive to gym

– Do 3 sets of dumbbell chest press

– Do 2 sets of incline dumbbell chest press

Wednesday

Diet

– Hit macros within +/- 3%

Training

– Put on workout attire

– Get in car

– Drive to gym

– Do 3 sets of barbell squats

…

etc.

Now here’s the important part. Just get through your list without thinking about outcome whatsoever. It doesn’t matter if you’ve completely lost all of your strength (which you likely didn’t) or if you’re still up 10 lbs on the scale. Focus on getting through your checklist.

Whenever you feel that voice inside of your head reminding you of where you once were, gently refocus back to your checklist and remain in the present.

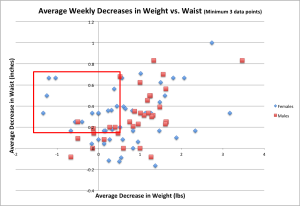

By the end of the week, you’ll have your totals for your major lifts, as well as your weight and waist measurements.

Step 5. Crush your previous baseline

That’s it. Once you beat all of reboot week’s previous totals, you will have re-established a positive feedback loop and you’ll be ready to keep kicking ass.